REVIEW: How to Solve It, by George Pólya

How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method, George Pólya (Princeton University Press, 1945).

Would you like to be smarter? Apparently many people would. There are people who spend much of their waking lives grinding at something called “dual n-back” to try to make themselves smarter. There are people who dose themselves with Chinese research chemicals to try to make themselves smarter. There are even some losers who spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on something called “college” to try to make themselves smarter. Meta-analyses have not shown any of these methods to work, but I am a lib and believe that people have a right to experiment on themselves (except for that “college” thing — that’s too socially destructive for me to condone).

More interesting are the numerous venture-backed startups aiming to help you have smarter kids by throwing away your dumb kids for you. These are fascinating because they’re like a laser-guided bomb aimed at one of the central contradictions of our state ideology. On the one hand, we are (officially) an egalitarian society. On the other hand, we (unofficially) treat intelligence as a proxy for moral worth, especially in educated upper-middle class circles. We square this circle by (officially) proclaiming that everybody is really about equally smart, it’s just that some of us (lib version) were privileged with more opportunities to do dual n-back during preschool or (con version) had the grit and fortitude and bootstrappiness to grind dual n-back instead of smoking dope. Nobody actually believes these stories, but we all pretend to, and then here come the embryo selection startups crashing through the wall like the Kool-Aid Man yelling: “LMAO, IT’S ALL JUST RANDOMNESS PLUS WHO YOUR PARENTS ARE.”

And there it is, the poisoned splinter buried deep in the wound, surrounded by inflamed and necrotizing flesh: some people are just smarter than others. It offends every notion of fairness we have, fills the privileged with guilt and the overlooked with rage: some people are just smarter than others. We fear that admitting it would open the door to countless horrors: revolution or genocide or a new caste system maybe, so we bury it beneath a thousand educational interventions: some people are just smarter than others. And as with every other case where the official doctrine and the unofficial rules diverge, it’s a tax on those unable to read the social cues. The chumps chase mirages like dual n-back or educational equity, while the savvy prosper because they hold the secret knowledge: some people are just smarter than others.

I was raised outside of the United States, in a society much less anguished about the fact that some people are just smarter than others, so I was a bit shocked when I came here and encountered the taboo, and then the reaction to the taboo. On this topic, Americans are like the kids with sheltered upbringings who go totally berserk in college. One small taste of liquor and suddenly they’re doing utterly freakish things like taking IQ tests or posting about “elite human capital.” If there’s anything worse than officialdom’s blindness to one of the fundamental dimensions of human variation, it’s the smugness of those who’ve figured out the truth and now act like they belong to a secret society and like it explains everything. They tend to treat intelligence as a kind of mystical gift, both vastly overstating its importance and assuming that if it’s innate then it can never be improved.

Fortunately they’re wrong about that last part. You can totally make yourself smarter. You don’t even have to do dual n-back.

But before we get to that, what does it even mean to be smarter? This is not a flippant question, I think we have no idea what we mean, because we don’t understand what intelligence is. Sure, we know it when we see it. Chimpanzees use tools in the sense of poking sticks into anthills, whereas human beings use tools in the sense of extreme ultra-violet lithography, and presumably intelligence is the thing that makes the difference. But what is that thing, and how can you have more or less of it? We’ve quantified things like working memory and the speed with which you can carry out reasoning steps, once you can reason at all. But is that really the whole difference between you and Einstein, or for that matter between you and the chimpanzee? It sure seems like between a human genius and a dumb human, and again between a dumb human and a chimpanzee, there is something qualitatively different, some fire from the gods that enables the smarter one to think in a new kind of way and to leap across chasms that the dumber could not traverse even if given aeons to do it.1

Let me do something very unusual for me, and recommend that we adopt a kind of methodological positivism. Let’s shift our point of view from the internal subjective experience of intelligence (“what does it feel like to have received the fire of genius from the gods?”) to the external objectively verifiable effects of intelligence. This immediately suggests a nice concise definition: intelligence is the ability of an agent to achieve its goals. I like this definition because it lets us sidestep all the boring arguments about book-smarts vs. street-smarts, etc. Intelligence is the thing that enables you to act upon the world and get your way, whether that’s via social manipulation (like convincing a posse to come with you into a spooky alley), formal reasoning (like inventing a new kind of physics that lets you build a plasma rifle to carry into the spooky alley), intuition (like having a funny hunch that there’s a mugger hiding behind that dumpster), empathetic reasoning (like putting yourself in the mugger’s shoes and realizing that he’d probably have a friend covering you from the second-story window), or all of the above tied together with a crafty plan.

I like this methodological move, because it lets us stop wondering what’s happening inside the sealed alien artifact, and start just measuring its power output. It also shows us how to increase that power output. Imagine instead of brains we have armies. If your army is overwhelmingly huge, you can win with a frontal assault. But you can make even a small army many times more effective by giving it a strategy. It’s the same way with big brains and small brains. Richard Feynman was famously able to solve problems with the “Feynman algorithm” (write down the problem, think about it a bit, write down the solution). But the Feynman algorithm is a handicap, we don’t need to use the Feynman algorithm! You’re allowed to come at the problem with a roadmap and a battle plan, and by doing so you are boosting your effective intelligence many times. You will solve problems that you could not have solved before, act upon the world and get your way in situations that you could not have won before. Perhaps you don’t have any more of the inner fire from the gods, perhaps you still won’t feel like Richard Feynman, but our external measuring device can’t tell the difference. Your power level is still over 9,000. You’re still winning.

Actually, I tricked you in that last paragraph. The “Feynman algorithm” was a story told by one of Feynman’s peers. Here’s how Feynman himself once described his secret:

I got a great reputation for doing integrals, only because my box of tools was different from everybody else’s, and they had tried all their tools on it before giving the problem to me.

This is a book about assembling your box of tools.

As with many classic works, you have read this book a thousand times even if you’ve never read it, like how Shakespeare and the Bible are full of clichés. It’s a sign of Pólya’s total cultural victory that his method has just sunk into the background of twentieth-century mathematical and scientific culture. I kept bumping into the mental tricks I use at work or the techniques I use when teaching my kids and going: “wait that’s where that came from?” So what follows might already be familiar to you if you come from that culture. But if like me you were raised as a “Christmas and Easter” mathematician/scientist and have only encountered these ideas in fragmentary and sublimated form, it’s still quite useful to see them laid out systematically and unapologetically.

Pólya’s book is about what to do when you encounter a problem. Not an exercise, mind you, but a problem, and if you have no idea what distinction I’m trying to make, I lay it out at some length here:2

Pólya is a mathematician (I first encountered him via his wonderful enumeration theorem in combinatorics), and his examples are largely drawn from the world of mathematical proof. But the thing about Pólya’s method is it applies far outside of mathematics, and I will try to motivate it with a wider set of examples. He divides problem-solving into four essential stages:

Understanding what it is you’re trying to do.

Coming up with a plan.

Carrying out the plan.

Reflecting on how it went.

Each of these stages deserves an entire essay, or perhaps an entire book, but let’s breeze through them so we can get to the fun part. The first step is understanding what you’re trying to do, and we can consider this at several different levels of abstraction. At its most basic, this is just understanding the ingredients you have to work with and the result you’re trying to achieve. Pólya analogizes mathematical problem-solving to building a bridge over a river. You have a starting point, and you have somewhere you’re trying to get to, and you cannot begin to build the bridge until you clearly see them both. What is the ground like in both places? Are the elevations different? Is there an obstruction in the middle? You wouldn’t think of building a bridge before you had surveyed the site.

Mathematics is a funny domain for studying the theory of problem-solving. One unusual thing about math is that if you understand your starting point and your ending point sufficiently well, then you’re already done.3 And in fact, a lot of very good mathematical work happens in this initial site-surveying phase. Sometimes something as seemingly-superficial as the introduction of notation is enough to get the entire job done (I keep waffling back and forth on whether this says something incredibly deep about the nature of reality or not). The farther up the stack you go — towards physics, or engineering, or military strategy, or B2B SaaS — the less likely it is that the entire problem will dissolve when you reframe the question, but… sometimes that still happens. Even when it doesn’t, looking at the problem from another angle may yield shocking insights, but to do that you need to rotate it, and to rotate it you need a good grasp on it.

The best possible grasp comes from inventing the problem yourself. But if you were assigned the problem by somebody else that’s okay, you can achieve most of the same benefit by reconstructing or reframing the problem in your own mental language. You have a better shot at noticing that a problem can be rewritten or transformed into a much simpler representation if you really inhabit it. You need to live and breathe the problem, and let it drive you a little bit crazy, only then can you be sure that you really understand what it’s asking (and once you start dreaming about the problem, good news! That means your subconscious is now working on it too, we will come back to this.)

If your site survey stops with a thorough understanding of the problem, you are still missing out. In real life, as opposed to artificial school environments, problems do not come neatly packaged up and delivered to us. A yet more profound question you should be asking yourself is: “do I need to be solving this problem?” Remember that intelligence is the ability of an agent to achieve its goals. If the goal in question is instrumental, do you really need to do it? And if the goal is terminal, is there some other way to achieve it? Do you really need to build this bridge? Can you walk a mile upstream and use somebody else’s bridge? Can you take a boat? Do you even want to be on the other side of this river anyway?

Some problems come to us demanding to be solved, like an invading army or a looming bankruptcy. But others we go hunting for because they are economically or intellectually valuable. Or for sport. An entrepreneur and an academic are both a kind of truffle-pig for good problems, and it pays to develop a nose for them. Eventually you learn to notice its spoor, the rank taste in the air, “a problem has passed by this way, moving downwind, two days ago.” One of the many ways school fails us is by actively harming this capacity, it lies and lies to us for decades, teaching us that good problems will be delivered on a silver platter. This is why so many people who do well in school never amount to anything. They never develop a taste for the hunt, never learn that this, actually, is the most important part of the entire site survey: “is this problem worth solving by anybody?”, “am I uniquely well-positioned to solve it?”, “can I amass the resources to solve it?”, “do I have any chance of success?”, “is there some other problem that it is more valuable for me to solve?” The greatest lie that textbooks teach is that the hard part is coming up with an answer. No, the hard part is usually coming up with a worthwhile question.

I’m temperamentally very bad at completing a proper site survey. My inclination when faced with a problem is to charge in screaming and waving a sword naked with my body painted blue.4 That means I’m bad at the second step as well, which is: forming a plan. Going back to our bridge analogy, this is the part where we build the bridge in our minds, first hazily and intuitively perhaps, a mere idea of a bridge, then proceeding through several stages of reification and concretization into something as crisp as blueprints or as real as scaffolding.

Once again, mathematics is a weird domain for analyzing the nature of problem solving. This time, because step 2 and step 3 can blur together at the edges. Anyone can see that planning a military campaign and actually conducting a military campaign are very different things, but when you’re attacking an algebraic expression rather than a city, sometimes once you’ve come up with the plan the rest is practically a formality. This particular idiosyncrasy, however, is more true of the “math” you do in high school, and a lot less true of “real math.” When proving a big scary theorem, planning and execution are very different kinds of activities.

For starters, you’re allowed to be sloppy when planning. Guessing at a solution is totally permitted, as is reasoning via vague or conceptual analogies from other areas.5 Generally speaking, the more painstaking and precise we are when executing the plan, the more wild and unprincipled we’re allowed to be when conceiving it. There’s an analogy here to the thing where the easier it is to verify the output of an AI system, the more economical it is to use an AI method that produces lots of wrong answers.6 Math is an extreme example of this: when you come back to flesh out your argument and give it bones, clearing away all the scaffolding and letting the bridge stand on its own, your methods have absolute certainty. That means you can be as hare-brained in your idea generation as you want. (The same is not true of planning a military campaign, where the cost of validating your plan is much higher.)

Non-mathematicians often confuse the planning and execution stages of mathematical (or other very theoretical) work. The great Jacques Hadamard, in his fun little essay “The psychology of invention in the mathematical field,” mocks the normies who think that mathematicians do their work by manipulating algebraic symbols according to logical rules. No, he explains, mathematicians check their work by performing calculations. The actual solution came another way: a sudden insight connecting two disparate ideas, or an intuitive leap, or a visual depiction of the problem, or just a weird hunch. Those are the sources of inspiration, but they’re often wrong, so then we break out the x and the y to check that our hunch was correct. This is more akin to step 3: executing the plan, making it real in all its gory detail. But we can’t start there, we would never have been able to solve the problem just by staring at x and y on the page and willing them to dance.7

Some of you may be furious at how apophatic this description is: “okay, figuring out how to solve something isn’t about moving around x and y, so what is it???” But I’m not just being cute, stage 2 is by far the most mysterious phase of the process, the part where we are most likely to start babbling about genius and the divine spark, the part where even history’s greatest problem-solvers fail to introspect and give a coherent account of what happened. Hadamard, having finished mocking others, is just a trifle embarrassed when it’s time for him to advance his own theory. “I dunno, you just need to think really hard about it,8 and then go off on vacation and let your subconscious work on it.” There’s probably something to that advice. You could also go sailing instead. But can we do any better than that?

This is where your mental toolbox comes in.

Pólya’s great contribution to the art of problem-solving is a list of completely general problem-solving heuristics combined with a completely general heuristic approach. Putting the two together, you can solve any problem. You just employ the tools according to the approach. Let’s talk about the completely general heuristic approach first, because it’s shorter. Are you ready? Here it is:

“Take a tool out of your toolbox, and spend a few days whacking it against your problem. If you don’t get anywhere, put it back and repeat with the next tool. If you run through all your tools, start again from the beginning.”

Now, the only remaining work is to enumerate all the tools (mathematicians love talking this way, and yes it’s aggravating). Pólya uses the word “heuristics,” I’ve been using “tools,” but some of you may prefer to think in terms of “moves” — like the actions your character can take in a computer game. Some moves are domain specific. If you’re a martial artist and your opponent has you pinned to the mat, there is a set of literal moves you can do, one of which may solve your problem. If you’re flying a fighter jet and the enemy is on your six, there are some moves to consider: like shedding altitude to gain speed, doing a barrel roll, or ejecting. Computer programmers and corporate managers have their own moves: would adding a layer of indirection or reorganizing the department help here? And yes, mathematicians have moves as well.

If he were a lesser man, Pólya might be content to teach a few of those mathematical moves, but the curious thing about math is that it’s so close to the stuff of pure thought itself, that by putting in just a bit more effort Pólya is able to refine these mathematical moves into completely general problem-solving heuristics. That is moves that work not in one domain, but in all domains. Moves that spawn new moves. Meta-moves. The bulk of his book is a vast list of them. Once again, an entire essay (or an entire book) could be written about each of them. But I’ll confine myself to a few sentences about a small number, so you get the flavor.

Does this problem remind you of another one? The easiest problem to solve is one that you’ve solved before. Maybe it isn’t exactly a problem you know, but it could be related, or it could be cleverly disguised. A lot of “crystallized intelligence” is really just having a large corpus of related problems in your history, and being good at relating or transforming new problems into old ones that you’ve already conquered. This is one reason I think some human triumphalism over AIs memorizing their training distribution is misplaced — if that distribution is sufficiently large and general, and if you’re sufficiently good at pattern matching against it, then this is a wickedly powerful tool. One way to view it is that this is the meta-technique that lets AIs be very effective even without much “intelligence,” but another way is that more of human intelligence than we want to admit is actually just this. Either way, if you want to boost your effective intelligence you should probably get good at this.

Example: You and your men are outnumbered and trapped at the bottom of a valley, with a forest to your left, and a marsh to your right, the enemy holding the high ground ahead of you. The situation looks grim, but wait a minute, that sounds a lot like one of Napoleon’s battles which he was able to win with a really innovative approach. Hmm… but it’s not exactly the same, because on that day Napoleon’s opponent didn’t have artillery superiority, but your opponent does. But if there were a way to neutralize that artillery superiority or make it not matter…

What would make it easy to solve this problem? There’s an old joke used to make fun of an academic discipline that you want to mock as being overly theoretical: a mathematician/philosopher/economist/whatever is trapped on a desert island with a bunch of canned food that they need to open, so they say to themselves: “assume we had a can opener…”. This joke is stupid, because “assume we had a can opener” is exactly the right problem-solving step if YOU HAVE A WAY OF GETTING A CAN OPENER. In real life, as opposed to desert islands, there is usually a way to make or borrow or buy or steal or invent whatever thing it is you might need. “What tool, if I had it, would make this easy” is an incredibly productive thought most times, because it allows you to break the problem down into two easier subproblems. You can also generalize this to “what is an alternate situation where I would be one step away from victory?” Then you see what it would take to get yourself into that situation, and recurse as necessary. (This is a very familiar line of thinking for people who like Chess puzzles, but it applies to much of life.)

Example: You can’t get a date, because none of the women at this club will talk to you. This would be a lot easier if you were more charismatic and in better shape. Are there ways for you to become more charismatic and get in better shape?

How do you know this isn’t impossible? If you’re trapped by a problem, in your research, or in business, or on a military campaign, and you can’t figure out any way to free yourself, try turning the tables on yourself and prove that it’s impossible for you to win. Note that this is not the same as avoiding impossible problems in stage 1 (the site survey), we are assuming here that we’ve chosen a solvable problem, but we’re going to pretend it’s impossible anyway. Why? Because we might learn something from how and where our impossibility proof eventually fails. There will be some crux. Some moment it can’t connect and all turns to ash. Study that moment, it may be the key to your original problem. The adversarial equivalent of this is putting yourself in the enemy general’s shoes. What is the move you can make that there’s no way for him to plan for or respond to? That’s your move.

Example: It’s your move in a chess game and you’re in a horrible position. You can feel the net tightening around you, and you don’t know how to escape. So you turn the situation around, and think about how your opponent can force a checkmate. All of the paths to checkmate hinge on attacking one particular square. You return to your side of the board and see that there’s a method of defending that square which blocks every checkmate and lets you escape the trap.

Can you restate the problem without using any of the same words? This is a classic way to unstick yourself when in a rut. It originates in mathematics, where in some sense having a suitably deep understanding of a problem means you’re already done. By replacing terms in the problem statement with their definitions, and then swapping them out for other equivalent definitions, and so on, you often jog something loose and give yourself the perspective you need. Often, changing all the words is what makes you realize that the problem is something you’ve already seen in disguise (see above). But the same technique works sneakily well outside of math as well.

Example: You are a tech founder experiencing self-pity. “My problem is that this venture capitalist won’t give me money.” Well, what is a venture capitalist? A venture capitalist is a professional money manager who expects a certain return profile on a certain timeline. So you can restate the problem: “My problem is that this professional money manager who expects a certain return profile on a certain timeline won’t give me money.” Notice how the second formulation is more pregnant than the first, it is already suggesting courses of action and angles of attack. Now you should try it again with several other definitions of venture capitalist, and suddenly instead of self-pity you have potential plans.

Can you solve an easier problem? You feel that this problem is too hard for you. That’s okay, try making it easier. Can you solve the easy version? Okay, now see if you can adapt that solution so it still works for the original problem. This approach works best when the easier problem either strips away distracting details and chaff while preserving the crux (now exposed and open to your attack), or when the reduction to an easier problem preserves some essential structure of the grander case as with mathematical induction. Yes, this is closely related to “assuming a can opener,” since giving yourself a tool or putting yourself in a better position is one way to make a problem easier. Even if this doesn’t directly help you solve your problem, Pólya says you should do it anyway because it may steel your spine and renew your courage.

Example: “Find for me the length of the diagonal of a rectangular prism with known side lengths.”

“I can’t do it, I’m not good at math.”

“Okay, well can you find the length of the diagonal of a rectangle with known side lengths?”

“Yeah, I’d use the Pythagorean Theorem!”

“Amazing, so you can do this for a 2D box, now see if you can figure it out for a 3D box.”

“Hmm…”

Can you solve a harder problem? This one surprises people, but sometimes making a problem “harder” in the sense of more general or more all-encompassing can make it easier to solve. The absolute master of this technique was Alexander Grothendieck who specialized in solving problems by zooming out and out and out and out until the original question was barely visible and then proving some massively more profound theorem that incidentally settled the starting problem as a consequence. This happens so often in mathematics that Pólya calls it the “inventor’s paradox” and gives many examples of it, but there are examples outside math as well. Anytime it’s easier to step outside or entirely replace a system than to work within it, you are making a problem easier by making it “harder.” And there are countless businesses that would have a better shot at surviving if they were 10x larger, or also did the jobs of all of their suppliers. It’s a sad truth that a great many plans fail because they were insufficiently ambitious.

Example: You want to achieve some political change that’s opposed by powerful interests. If you win a narrow electoral majority, progress will be slow and your opponents will constantly be trying to peel off the least committed members of your coalition. It may be impossible to achieve your goal this way, but possible if you win a landslide majority that allows you to act without restraint.

The bulk of the book is a glossary of dozens and dozens of such heuristics or tools or moves, with examples (mostly from math, but also a few crossword puzzles and word-related brainteasers) of how to employ them. Pólya doesn’t list each heuristic as a question like I have, but I think he’d approve of this choice, because he thinks that while you’re grinding on a problem you should have questions like this running on a loop in the back of your head. Questions like these are also how he thinks problem-solving should be taught to the next generation — when a student is stuck, the teacher shouldn’t give any hints, but just keep asking things like: “have you seen another problem like this before? could you try solving an easier version? what would make it easier to solve this problem?”, etc. The goal of his technique is that after a while, the student stops requiring the teacher to ask these questions out loud, because they have become part of their own internal monologue. This is the part where I laughed, because I instantly recognized that this was what my best teachers had done to me, and what I have automatically and without reflection done when teaching my own kids math. Like I said, total cultural victory.9

So we’ve made it through step two, and our bridge now has a blueprint, or perhaps even some scaffolding. Now it’s time to execute on the plan, and you might ask what this possibly has to do with intelligence. Sure, coming up with a plan takes brains, but putting it into action is more likely to tax our backs than our creativity, right? Oh sure, there are some restricted domains (like math, writing, computer programming, maybe a few others) where the execution itself just looks like further thinking, but surely those are weird exceptions, right?

Wrong. It would be so, but for the fact that no plan survives first contact with the enemy. The moment you start building the bridge for real, carrying bricks, things will start to go wrong. The ground on one of the banks of the river is squishier than you thought, or you can’t properly sink the foundation for the main pier holding up the span, or the materials you thought you had are actually something else. No plan is ever good enough, it happens in every domain, in math and in programming and in business and in writing and in strategy games and in actual wars. You’re following the plan, and suddenly it dawns on you with a chill: “oh crap, this isn’t going to work.” And so you’re thrown back into stage 2 or even stage 1, but with a crucial difference: your bridge is half-built, it’s teetering out there in the wind, and you’re exposed, bullets zipping over your head. It’s time to solve the problem again, but this time while panicked and rattled and under pressure.

There are some very foolish people, mostly in the tech industry, who have taken the observation that no plan ever works without modification, and drawn the conclusion that therefore planning itself is pointless. Better, they say, not to plan at all and just do your best. But that’s just going back to the Feynman Method which if it works for you, great, congratulations, I’m very happy for you. For those of us who need to boost our intelligence by unnatural means, however, planning remains essential, we just need to slightly complicate Pólya’s four stage schema. The truth is that execution and planning aren’t really distinct, rather they feed off each other in a loop. You get halfway down the path and discover why your plan isn’t so good, and gather new data that informs your attempt to re-plan. It goes the other way too — sometimes in your planning phase, you do little scouting expeditions to inform the plan, and sometimes one of those forays catches fire and starts to work and you’re executing without realizing it.

Another way of conceptualizing this is that the difference between the planning phase and the execution phase is not actually the activity, because in both phases you’re engaged in a mixture of both planning and execution! The difference, rather, is the tempo. The planning phase happens before the die is cast or the ships are burnt, whereas the execution phase is more dynamic. There is the kind of thinking where you can take another week to come up with a marginally better solution, and the kind of thinking where a solution in a week is no solution at all. Many of the same heuristics and mental tools we discussed before will still work here, but you need to apply them quickly, on your feet, maybe while your opponent is making countermoves or the world threatens to leave you behind. And if the moves don’t work, or don’t work on the schedule you need, then too bad you still need to do something.

I was embarrassingly old when I figured out that endurance is an intellectual virtue. I’ve written at some length about this before, but for the longest time I believed that the way to tell you were good at solving problems was that you figured out all the answers right away. The truth is that when faced with a real problem, so much of what determines your success is not raw mental horsepower, but your ability to grit your teeth and hang in there. When you’ve failed to solve it a dozen ways and promising leads have turned into nothing and you’ve landed back at square one again, it takes a very particular quality to pick yourself back up and charge at the problem with as much energy and excitement as you had the first time.10 As Pólya puts it:

Lukewarm determination… may be enough to solve a routine problem in the classroom. But, to solve a serious scientific problem, willpower is needed that can outlast years of toil and bitter disappointments.

…

Teaching to solve problems is education of the will. Solving problems which are not too easy for him, the student learns to persevere through unsuccess, to appreciate small advances, to wait for the essential idea, to concentrate with all his might when it appears. If the student had no opportunity in school to familiarize himself with the varying emotions of the struggle for the solution his mathematical education failed in the most vital point.

He calls it willpower, but I think it can be more akin to physical pain tolerance, or the capacity for asceticism. The startup people call it “grit” these days, an ability to absorb setbacks and persevere.11 But when you’re into the execution phase and the bullets are whizzing past you, your ability to bounce back from setbacks doesn’t just depend on endurance, it also requires courage. Picking yourself back up when your plans have all crashed to the ground for the tenth time has a different feel to it when your enemies are closing in, which is why we have more respect for Napoleon than we do for a long-distance runner. Mere endurance is different from doing whatever it takes to find the move that lets you survive one more day. This distinction is why some people who are very good at phase two of solving a problem struggle with stage three, and vice versa.

Let’s suppose you survive the execution phase. Your bridge is built. (There was a dicey moment in the middle when you had to battle a shark, but it turned out okay.) Are you done? No. If you stop here you will merely have a bridge, but you will have squandered the far greater prize of reflecting on all that you learned while building it. This is where the real leveling-up happens, and it’s why every high-functioning organization conducts after-action reports of some sort. Are you a high-functioning organization? I hope so!

Once again it’s illuminating to see how mathematicians approach this. A very common piece of mathematical advice is “when you’ve finally proven a theorem, go back and prove it again differently.” How can that be? Wasn’t the proof the point? Sort of, but with the knowledge and insight you’ve gained from proving the result, you can often now go back and write a much better proof: cleaner, simpler, more direct, shedding more light on the true nature of the problem. Not to do this is an insane missed opportunity for consolidating and crystallizing your knowledge. Here’s Pólya:

When the solution that we have finally obtained is long and involved, we naturally suspect that there is some clearer and less roundabout solution… Yet even if we have succeeded in finding a satisfactory solution we may still be interested in finding another solution. We desire to convince ourselves of the validity of a theoretical result by two different derivations as we desire to perceive a material object through two different senses. Having found a proof, we wish to find another proof as we wish to touch an object after having seen it.

Two proof are better than one. “It is safe riding at two anchors.”

By solving a problem and meditating on it, we move that solution into our database of tricks to call on when confronted with the next problem. By solving it twice, or by looking back and with hindsight seeing how else we could have solved it, we get to contribute to our database twice for a small amount of additional effort. But we don’t just want to reflect on the solution. All the blind alleys, the false starts, and the setbacks start to pay rent here — each one of them is a chance to retrospect: “what didn’t I see?” “Why didn’t I see it?” What could I have done differently that would have made me see that sooner?” Each of our scars gets added to the database too, as well as the fact that we overcame them. If you’re a believer in growth mindset, this is your chance to do a little self-hypnosis: “look, I am the kind of person who overcomes difficult things.” Finally this phase feeds back into problem selection: “now that I have solved this problem, what new goals will be easy for me?”

I was being facetious when I described Pólya’s method as a completely general heuristic approach that lets you solve any problem in any domain.12 But I sincerely believe that following these steps or other steps like them, and painstakingly amassing a set of “moves” for your mental toolbox, and cultivating the virtues of endurance and courage, will massively increase your measurable intelligence in the sense of your ability to accomplish your goals and impose your will upon the world. I also think that this perspective could help answer two very profound and very important questions about intelligence: one about its past, and one about its future.

First, the past. Some ancient people were unbelievably smart. When you’ve finished watching the video Dwarkesh linked, read Pólya’s description of how Aristotle deduced with nothing but naked eye observation and logic that the Moon must be a sphere rather than a flat disc, and must shine by reflecting the light of the sun. So the question, put very bluntly, is why didn’t these intellectual beasts get any further? Before you say it, no, it isn’t because they lacked lab equipment. I once had a very stimulating conversation with a top physicist on the question: “could a sufficiently smart caveman have deduced general relativity from observation alone?” He maintained that the answer was yes. Even if you wouldn’t go that far, surely you concede that the caveman could have deduced Newtonian mechanics. And yet they didn’t. Even Aristotle, who was surely much smarter than the average AP Physics student, didn’t. Why is that?

The most sensible answer I’ve heard is sort of an intellectual version of the slow process of accumulating economic surplus in agrarian societies. Why do we read? It’s because we don’t have time to rethink every thought that was ever thunk. If Newton had to invent algebra himself, he might have died before inventing calculus. But he got to stand on the shoulders of giants, and we get to stand on his shoulders and many others besides. This argument sounds pretty reasonable in some ways, but I am not entirely satisfied with it. For starters, I think the ancient world’s rate of progress is still much slower than you would expect if this were the only problem. Okay, so you need somebody else to invent algebra and for those ideas to diffuse… why wasn’t calculus invented in 1400 then? Or in 1200?13 And it isn’t just calculus, there are so many ideas that were discovered centuries after they could have been.

Well, maybe the problem is just that they didn’t have Pólya’s method. Yes I’m being flippant here, but only a little bit. An overwhelming advantage that we moderns have is not just the finished intellectual products of earlier ages, but the numerous examples of exceptionally high-quality reasoning that produced them. In other words, the training data of a modern thinker is filled with a huge number of “moves,” heuristics, stories of how people figured things out. In Newton’s phrasing it’s not just that we stand on the shoulders of giants, it’s that we get to see how they got so tall in the first place. And I have a very strong hunch that it’s much slower to overcome a paucity of quality intellectual efforts to model your own on than to overcome a mere absence of knowledge. In complexity-theoretic terms, I think it should be asymptotically quadratic rather than linear (can you see why? Can you make my hunch precise?).

To that big barrier, we can add the further barrier that “moves” are harder and less rewarding to translate across languages and cultures than the final results. It’s easy for a Greek to explain Pythagoras’ theorem to a Chinese person, but much harder to convey the full spectrum of intellectual history and culture and arguments and inside jokes that got Pythagoras there. So until very recently, the slow accumulation of excellent training data for thinkers was being done by very small effective populations, further slowing this critical precursor to conceptual breakthroughs.

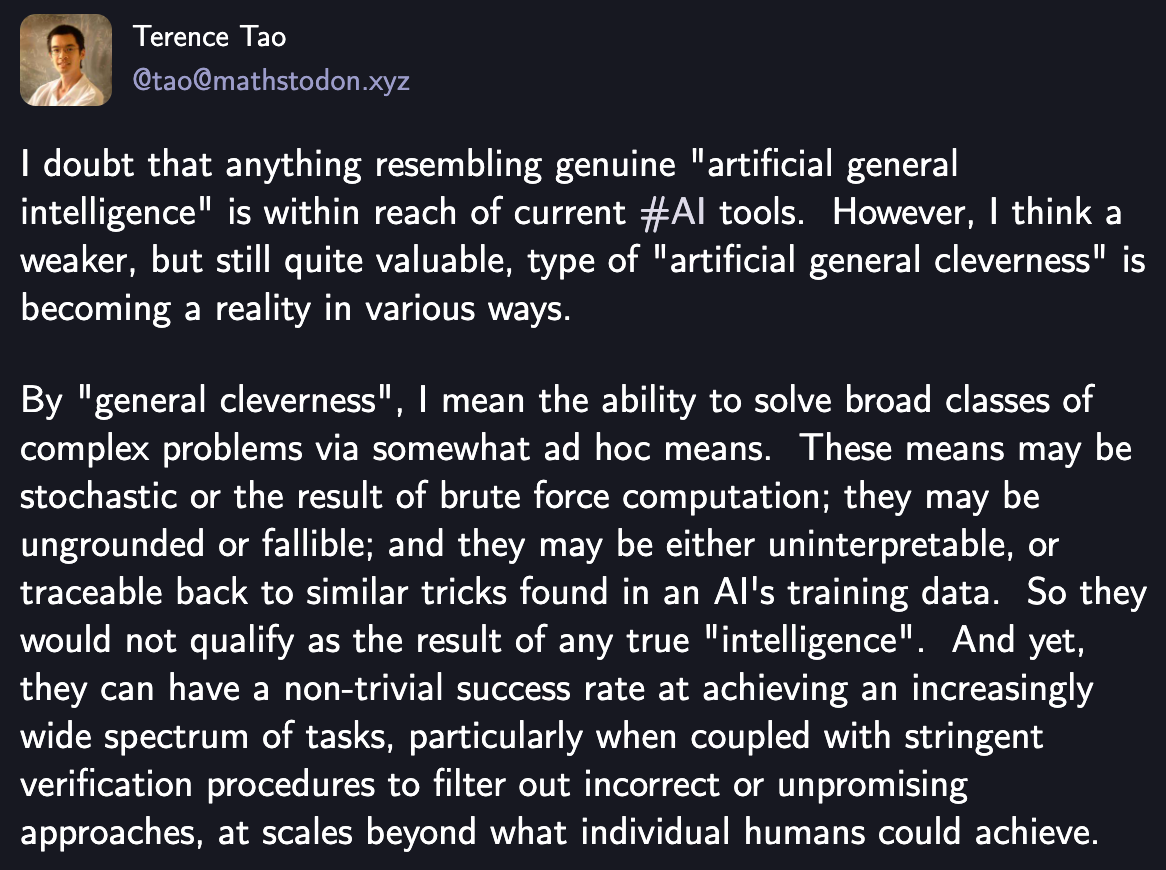

I’ve said “training data” a few times, so yes I think the other big question that Pólya’s method sheds light on has to do with AI. There’s an argument about the capabilities of language models, which I myself have made several times, which goes something like this:

Far be it from me to tell Terrence Tao (an actual, real-life supergenius) about the workings of his own mind. But if you’ve made it to the end of this book review, I’ve hopefully convinced you that a lot of human intelligence is also just “cleverness” of this sort. The saucy way of putting it is that human beings are not actually general intelligences, we’re apes with access to linguistic recursion (which means that the sticks we bang together can be arbitrarily complex), plus cultural evolution that has allowed us to amass an ever-growing pile of complex sticks that we can bang together… one at a time… No really, you have just read over 7,000 words about how an important problem-solving hack is relating the problem to something you’ve seen before.

It’s an interesting fact about language models that the more training examples you feed them, the smarter they are as measured by various benchmarks. People call this a “scaling law,” and claim that it holds true over many orders of magnitude. The haters and skeptics, of which I have at times been one, claim that this is just because as the training data set grows, the odds that it contains something very similar to the question you’re asking also grow. A very good skill at pattern recognition (I think we all agree that neural nets have that), plus a near-infinite memory, can probably get you exceptionally far at pretending to be intelligent. Maybe that’s all that’s going on?

Ah, but we who have been Pólya-pilled know that that training data contains something else as well. It’s the thing that Aristotle and the other ancients were missing. Reams and reams of examples, not of solutions to particular problems, but of exceptional problem-solving itself. Vast hordes of “moves,” a shimmering toolbox filled with high-quality heuristics. All that an agent needs to vastly boost its externally-measured intelligence in furtherance of its goals. Pattern recognition plus a good memory might help you “cheat” on a particular problem, but when conducted at the meta level it is the core of Pólya’s entire methodology: learning to recognize not solutions you’ve already seen, but approaches you’ve already seen.

I don’t know whether training on the distilled, high-quality reasoning behavior of millions of the brightest human beings will “really” make an AI smart. After all, I opened the essay by saying that I don’t know if it will “really” make you or me smart. What does it feel like to be a genius? To be Richard Feynman or Terrence Tao? To have the ineffable fire from the gods? I don’t know, but I’m also not sure it matters. Intelligence is the ability of an agent to achieve its goals. Let’s hope that theirs are in line with ours.

I think this qualitative and almost mystical view of intelligence underlies many of the apocalyptic hopes and fears around superintelligence. It’s not just that intelligent machines will think faster and have better memories than us (they will), it’s that they might have more of that mystical fire and divine spark, and that this might give them abilities that seem to us like magic.

Pólya is as dismissive as I am about exercises, which he calls “routine problems”:

Teaching the mechanical performance of routine mathematical operations and nothing else is well under the level of the cookbook because kitchen recipes do leave something to the imagination and judgement of the cook but mathematical recipes do not.

He also makes an interesting observation that the thing teachers hate where students don’t pause for a moment and think about whether their answer is ridiculous (like a word problem about a yacht where you get a solution saying it’s 16,310 feet long) is directly downstream of the artificiality and low-stakes of the setting.

I once had a supergenius Soviet émigré mentor who would drive us all batty with his classroom explanations. When, say, teaching a theorem, he would write the givens or the definitions on the blackboard, then stand there looking at it for a bit, purse his lips, then suddenly bounce on his feet and cry: “it’s obvious!” and write the conclusion without any intervening steps. He wasn’t trolling us, I think it really was just obvious to him.

I got my revenge on the final exam, where there was a problem I had no idea how to solve. So I wrote the givens, and then wrote the conclusion, and scrawled in the margin: “it’s obvious!” He marked the question correct, but deducted a single point with the note: “you should be more explicit about showing this step.”

It feels a bit like a personal attack when Pólya says: “An insect tries to escape through the windowpane, tries the same again and again, and does not try the next window which is open and through which it came into the room. A man is able, or at least should be able, to act more intelligently.”

Pólya cautions us — that analogical reasoning should only be used for hypothesis generation and then carefully checked — via the following parable:

The chemist, experimenting on animals in order to foresee the influence of his drugs on humans, draws conclusions by analogy. But so did the small boy I knew. His pet dog had to be taken to the veterinary, and he inquired:

“Who is the veterinary?”

“The animal doctor.”

“Which animal is the animal doctor?”

This is why I’m very optimistic about using LLMs for math and for things like image generation, where you can tell at a glance if it did what you want. Conversely, this is why using them for long-form writing or complex software is likely to cause you more trouble in the long run than you saved.

This also goes a long way to explaining what’s going on with a certain style of mathematical proof/argument that students really hate: where a totally unjustified deus ex machina appears out of nowhere and solves the problem. You may have felt this way in geometry class when a teacher introduced an auxiliary element into a figure, or in algebra or calculus when they did some crazy variable substitution. Hadamard’s point applies here too — these are ways of formalizing and making precise an idea that somebody had, but they are not themselves the idea. Pólya describes such “abrupt” feeling proofs as pedagogical failures. If a student feels this way about a lesson, it means you didn’t do a good job teaching them what the inventor of the technique was really thinking.

The thinking really hard part is mandatory. You can’t just go on vacation. Pólya:

Only such problems come back improved whose solution we passionately desire, or for which we have worked with great tension; conscious effort and tension seem to be necessary to set the subconscious work going…

Past ages regarded a sudden good ideas as an inspiration, a gift of the gods. You must deserve such a gift by work, or at least by a fervent wish.

Importantly, this is NOT the same thing as the Socratic method. They both involve questions, but they’re quite different. Socratic questioning is done either with the intent of leading the student to ἀπορία and the realization that they don’t know what they really mean, or in a leading manner to help a student discover aa truth on their own. (It’s supposed to be the former, but people doing “the Socratic method” often do the latter.) Pólya’s questions, on the other hand, are not meant to lead you anywhere at all, they’re meant to teach you the moves that will help you solve problems on your own.

Pólya notes that endurance is easier when we believe that there is a reason to hope. I have previously made everybody mad by pointing out that this is why scientists persist in a most-unscientific belief in a law-bound universe that is comprehensible to us.

Pólya also talks about the importance of being able to recognize when your making progress on a problem, both because it can serve as a guide for which avenues are most fruitful, and because it can help to keep your spirits up when you’re walking a long road. The funny thing about this is that if you’re trying to prove a new mathematical theorem, in some sense it should be “impossible” to tell if you’re getting close, because how could you without already knowing the answer? And yet I think every mathematician would tell you that there are “signs,” and Pólya spends a lot of time on how to recognize and read these signs.

Pólya is being a little bit facetious too. He later admits:

The first rule of discovery is to have brains and good luck. The second rule of discovery is to sit tight and wait till you get a bright idea.

It may be good to be reminded somewhat rudely that certain aspirations are hopeless. Infallible rules of discovery leading to the solution of all possible mathematical problems would be more desirable than the philosophers’ stone, vainly sought by the alchemists. Such rules would work magic; but there is no such thing as magic…

A reasonable sort of heuristic cannot aim at unfailing rules; but it may endeavor to study procedures (mental operations, moves, steps) which are typically useful in solving problems… A collection of such questions and suggestions, stated with sufficient generality and neatly ordered, may be less desirable than the philosophers’ stone but can be provided.

Do you even actually need algebra? One of my quack beliefs is that both Eudoxus of Cnidus and Archimedes probably figured out at least the basics of calculus but the knowledge died with them.

Sorry, complete tangent, but on the point: "Chimpanzees use tools in the sense of poking sticks into anthills, whereas human beings use tools in the sense of extreme ultra-violet lithography, and presumably intelligence is the thing that makes the difference."

There's a bit of a sleight of hand here; almost every chimp can figure out the stick in anthill trick after even a rough and quick exposure,, but how many humans out of 8 billion figure out Ultra-violet lithography even after being exposed to the idea in some depth? Is *individual* intelligence the real deciding factor here?

I'm reminded of the scene from I, Robot (the movie), where Will Smith asks the robot if it can write a symphony, and the robot replies "Can you?"

First, your definition would ruffle the feathers of many a self-proclaimed "genius" who purportedly crumbled under the pressure of parent/school and now work as retail clerks. Anyway, I was a terrible under achiever, and should have been held back, failing classes all throughout school and even the crummy regional college I later attended. Fortunately, the whole innate intelligence thing seemed to miss me as I was gearing up for the LSAT. Many people online said that one cannot meaningfully improve his/her own score because it's essentially a bunch of logic problems, with little to now formal "knowledge" tested. I refused to believe this and spent almost two years studying, getting terrible scores over and over again. But something inside me refused to believe that I couldn't get a good score if I didn't study hard enough. It never occurred to me, then, that maybe I just didn't have the stuff. I swear that over the course of studying, something changed. My brain came online or something. For the first time, I learned to problem solve, and like growing pains, it was anguishing initially, but by and by, my scores readily improved until I got a top percentile score. These habits followed me into law school, and allowed me to excel there, paving the way for my top-choice job. Certainly, I'd concede that there's outer limits, but improvement can happen, and our brains are a lot more adaptable than the innate camp would admit. There's no doubt such an "innate" mindset would have mentally crippled me had it taken stock back then.